How to Select the Most Relevant and Feasible KPIs to Measure Your Goal

by Stacey BarrToo often we feel paralysed in our search for the right KPIs. The best way to make progress toward the right measures of performance is to define “right” as the practical balance between strength with feasibility.

The perfect KPI rarely falls into our laps when we need it. Rather, when we try to choose the best performance measure for a specific goal or objective, we fall over a lot of unanswered questions. Like these questions from your fellow Measure Up readers:

- “How do you identify the right, most effective KPI’s to influence performance?” – Paul R., Australia

- “How do you identify the right KPIs that can be measured?” – Denise H., Canada

- “How do we know it’s the right measure?” – Natalie H., Canada

- “How do you handle KPI’s that you believe are great but you’re not sure you’ll be able to measure efficiently?” – Alf, Earth

- “I am trying to evaluate what is the best performance measure for the design engineering world?” – John K., Canada

- “What are the best indicators for performance measures, which are unambiguous and easy to determine?” – Emilia Z., Australia

- “How do I know that I have the best and measurable KPIs?” – Moeng S., South Africa

- “There are so many KPIs, how do you know which ones are the best fit for your organization’s needs?” – Katie T., United States

- “There are lots of KPIs, but how can we determine the best top 10 for C Level Executives?” – Jeff S., Canada

- “How do you know which is the best KPI to measure?” – Gail S., Australia

- “We collect a lot of data, but how do we decide which are the key measurements?” – Will H., United Kingdom

- “How can I choose relevant and meaningful KPIs that are easy to update every month?” – Effie G., Australia

It goes on and on. I get several questions like these every week. All these questions point to the same problem: not having a proper method to evaluate potential performance measures and select the best ones for a given goal or objective.

If we don’t know how to evaluate potential KPIs, we face two risks with the KPIs we end up with.

The first risk of not properly evaluating KPIs is that we throw away really good ones because we assume they’re infeasible to measure.

For example, a freight company needed to measure the accuracy of their inventory holdings. However, the huge volume of items, the number of sites, and distances between them, made the costs of even just sampling the inventory ludicrously high. But all we needed to do was redesign their sampling method, with help from a qualified statistician. Not only did the new sampling plan cost them much less to measure their inventory accuracy, but it also gave them a more reliable measure too.

The second risk of not properly evaluating KPIs is that we settle for really bad ones because they are super easy to measure.

There is no end to the examples that illustrate this risk. You see it readily in most organisations’ business or strategic plans. When you see milestones, trivial counts of activity, over-used traditional measures, and anything that was designed to fit existing data, you’re looking at the second risk in full swing.

We don’t have to expose our decision making about performance to these risks. It’s very simple to avoid them, by adding a few minutes to properly evaluate a potential measure before we adopt it or ditch it.

We need two criteria to evaluate potential performance measures: strength and feasibility.

In Step 3 of PuMP, we use the Measure Design technique to create and select the best KPI for a goal. Within the Measure Design technique is a special step that protects us from the two risks discussed above. It’s the step of evaluating our list of potential measures based on their strength and feasibility.

Strength describes how convinced we’d be that our goal was being achieved, just from that measure alone. It’s about how strongly correlated the trends and changes in the measure are with the achievement of the goal. For example, Number of Customer Complaints is a measure that has weak strength for a goal to increase customer loyalty, because the number of complaints can decrease (and look like improvement) simply because customers have given up complaining or gone to a competitor.

Feasibility describes the ease or difficulty of accessing the data we’d need for a measure. It’s essentially about the amount of time and money it will take to get the data. For example, the measure of Number of Customer Complaints is usually quite feasible because many organisations log complaints in a database, ready to count. But measuring customer loyalty directly might be less feasible if we haven’t already established a routine and statistically valid customer survey.

With our testing in PuMP implementations, we’ve found that the best rating scale to evaluate both the strength and feasibility of potential measures is a 7-point scale. And others’ research backs this up. Here’s a rough guide for how we set up the scales:

| Rating | Strength | Feasibility |

| 1 | the measure could signal changes in the opposite direction to how the goal is actually tracking | don’t have the data and it is impossible to get the data, at any cost |

| 2 | the measure could signal changes that correlate poorly with how the goal is actually tracking | don’t have the data and getting it is definitely more costly than we can afford |

| 3 | the measure could signal changes that don’t correlate strongly with how the goal is actually tracking | don’t have the data, and while we can afford to get it, the benefit isn’t worth the cost of getting it |

| 4 | could rely in part on this measure, but other measures are needed to track the goal | don’t have the data, but we can afford to get it and the benefit is worth the cost of getting it |

| 5 | could rely mostly on this measure, but another measure would be useful to track the goal | have some of the data, and/or can easily get all the data needed |

| 6 | could rely solely on this measure as sufficient evidence to track the goal | have most of the data, and can easily get the rest |

| 7 | could rely solely on this measure as complete evidence to track the goal | already have the right data for this measure |

While this is just one option, do make sure you set very extreme anchors for the ratings of 1 and 7, and be consistent about what’s inbetween. And do make sure you don’t over-think this tool, either.

Don’t over-engineer the ratings of strength and feasibility.

We use ratings to help us contrast and compare, to improve the logic of our decisions. The numbers themselves don’t mean too much on their own. They should give clarity and consistency to our conversation about which measures will be the best, but not make the decision for us.

There are a few useful ‘dos and don’ts’ for rating the strength and feasibility of your potential measures:

- Don’t attempt to rate a potential measure that is poorly written – make sure it’s a well-formed measure first.

- Don’t create weighted scores, like adding or multiplying the strength and feasibility ratings.

- Don’t give up if you don’t have enough data knowledge in the team – get input from other experts (see more about this below).

- Do use a consistently labelled rating scale for strength and feasibility, like the one shared above.

- Do discuss the rationales for each rating given, so the final selection of measures will benefit from the team’s collective experience and knowledge.

- Do aim for consensus in preference to averaging everyone’s individual scores.

- Do give more bias to strength than feasibility (see more about this below).

Ultimately, we’re trying to find the best balance between strength and feasibility so we can make useful and reliable decisions from the measure to achieve the goal. Again, we want to avoid those two risks:

- cheap measures that lead to the wrong decisions

- expensive measures that cost more than the benefits created by the right decisions

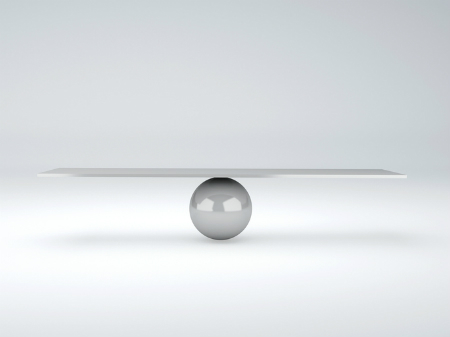

The optimal balance is between these two extremes, but it’s not in the middle!

The optimal balance gives more weight to strength, not feasibility.

Strength is more important than feasibility, because we often have more influence over feasibility than we first think we have. Additionally, if we don’t ever put the effort into to getting the data we really need but don’t yet have, we’ll never have the data we need. So, if potential measure A has strength 7 and feasibility 5, and potential measure B has strength 5 and feasibility 7, I’ll go with potential measure A.

If you’re really unsure about the feasibility of a strong potential performance measure, it’s worth giving that measure another chance. Or two.

The first chance you can give it is to take it a step further in the measurement process before making the decision. In PuMP, we take measures like this into Step 4, Building Buy-in to Measures. This step uses a technique call the Measure Gallery, which is largely about building buy-in to measures in a collaborative way. This collaboration often results in great ideas for improving the measures, including easier ways to get the data they require.

The second chance, if you’re still stuck, is go another step forward in the measurement process. This is Step 5 in PuMP, Implementing Measures. We use the Measure Definition technique here, and it will give you the chance to get more intimate with your potential measure, before you adopt it or ditch it, by defining details like these:

- The formula or calculation

- The data items you therefore need

- The potential sources of these data

- The frequency with which you want to measure

- What signals the measure must be capable of giving you

From these details, you get a broader appreciation for what data types and integrity you can still get good use from.

Aim for excellent KPIs, not perfect KPIs.

Perfect is lovely, but pursuing it is like chasing a mirage. Excellent is less than perfect, but pursuing it is progress. This holds true in every situation, and KPIs are no exception.

In PuMP we talk about the 80% rule, which means that when we’ve done a step in the measurement process to 80% of perfect, it’s time to move to the next step. Otherwise we stall, stagnate, and then surrender. We’re better off with excellent KPIs or performance measures that can help us make better decisions, than we are with perfect KPIs we can’t implement.

Aim for excellent KPIs, not perfect KPIs, by finding the practical balance between their strength and their feasibility.

[tweet this]

TAKE ACTION:

Next time you have a list of potential KPIs you must decide on, put them through the strength and feasibility filter to select the best one (or two) for your goal.

Connect with Stacey

Haven’t found what you’re looking for? Want more information? Fill out the form below and I’ll get in touch with you as soon as possible.

167 Eagle Street,

Brisbane Qld 4000,

Australia

ACN: 129953635

Director: Stacey Barr